Tensor Parallelism#

In this example, we will explore how tensor parallelism (TP) works in MLX. We

will start with an overview of the distributed layers in mlx.nn and then

show how to do tensor parallelism Llama-style transformer models.

Useful Design Choices#

The design choices above regarding when operations are done automatically are intentional and make model training and inference easier.

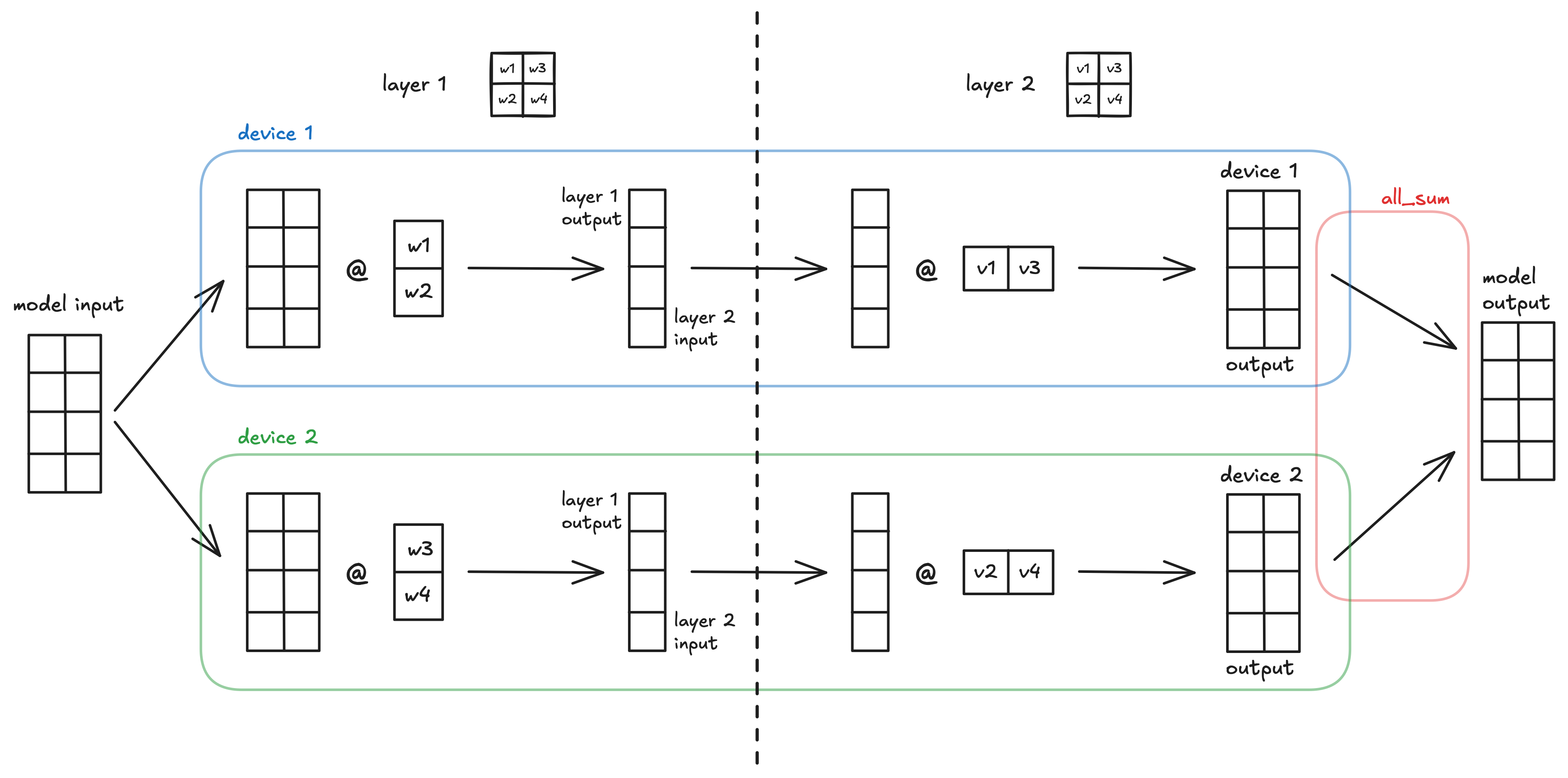

All-to-sharded and sharded-to-all layers naturally go together because the output of the former layer is exactly the input needed needed for the latter. This removes the need for an intermediate gather step between the layers, reducing communication overhead.

This is why mlx.nn.AllToShardedLinear does not aggregate results

automatically and why mlx.nn.ShardedToAllLinear does not shard inputs

automatically. It is so that they can be placed in successive order and work

together easily.

We can demonstrate this through a simple model using our two types of distributed layers.

x = ... # some (4, 2) model input: batch size 4, feature size 2

l1 = nn.AllToShardedLinear(2, 2, bias=False) # initialize the layer

l1_out = l1(x) # (4, 1) output

l2 = nn.ShardedToAllLinear(2, 2, bias=False)

l2_out = l2(l1_out) # (4, 2) output

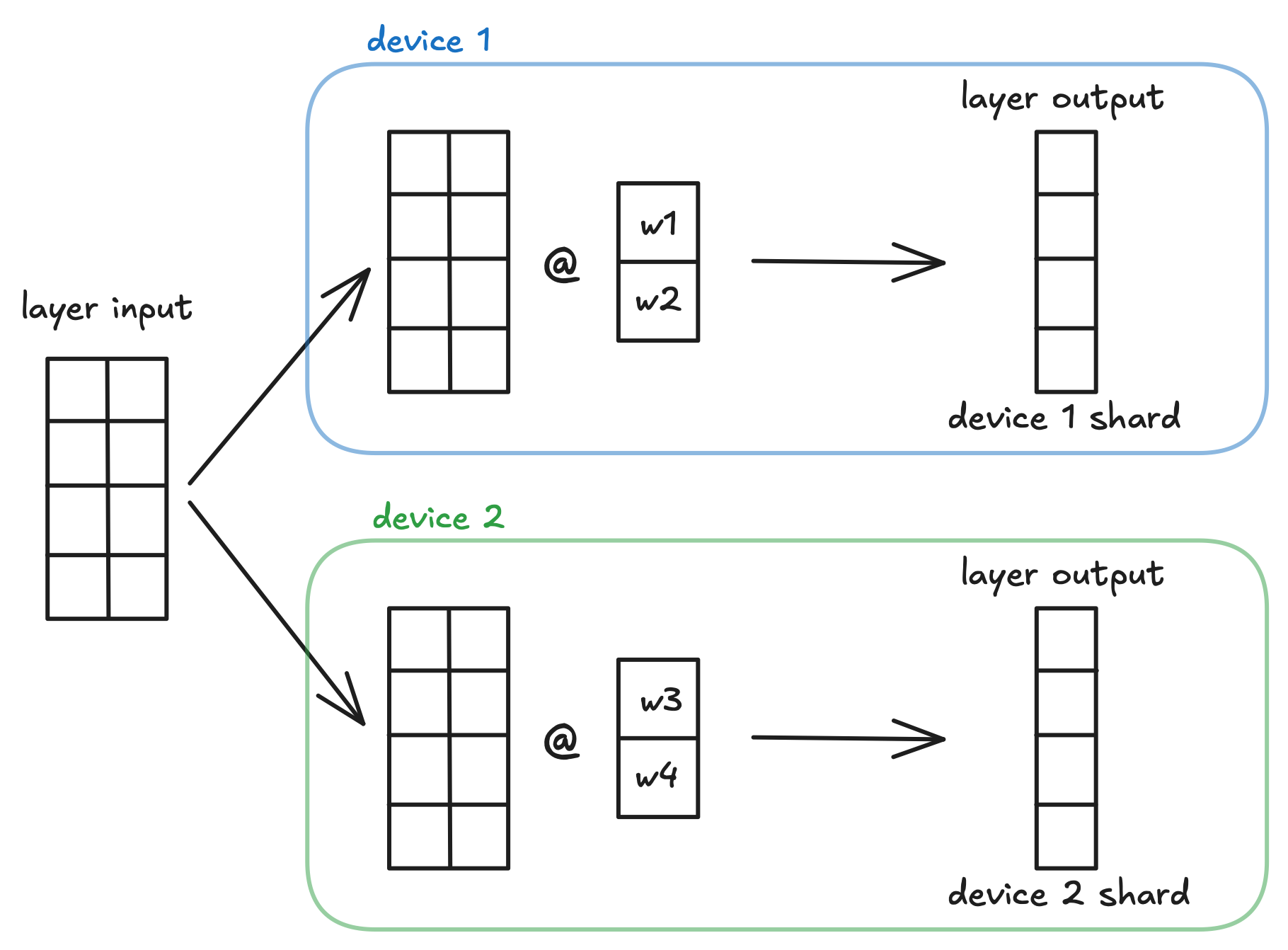

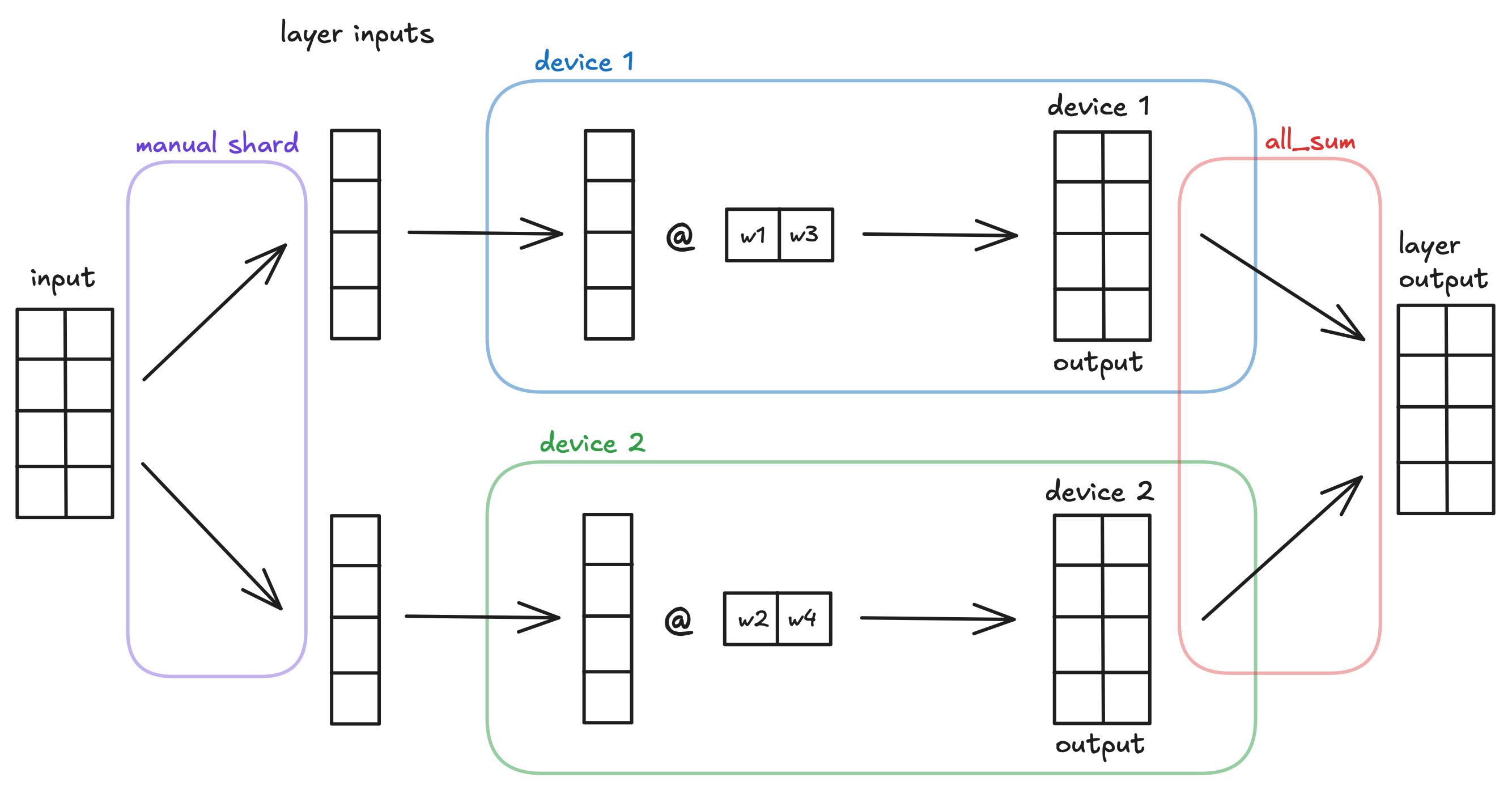

A visualization of the simple MLX model using all-to-sharded then sharded-to-all tensor parallelism across 2 devices.

LLM Inference with Tensor Parallelism#

We can apply these TP techniques to LLMs in order to enable inference for much larger models by sharding parameters from huge layers across multiple devices.

To demonstrate this, let’s apply TP to the Transformer block of our Llama Inference example. In this example, we will use the same inference script as the Llama Inference example, which can be found in mlx-examples.

Our first edit is to initialize the distributed communication group and get the current process rank:

world = mx.distributed.init()

rank = world.rank()

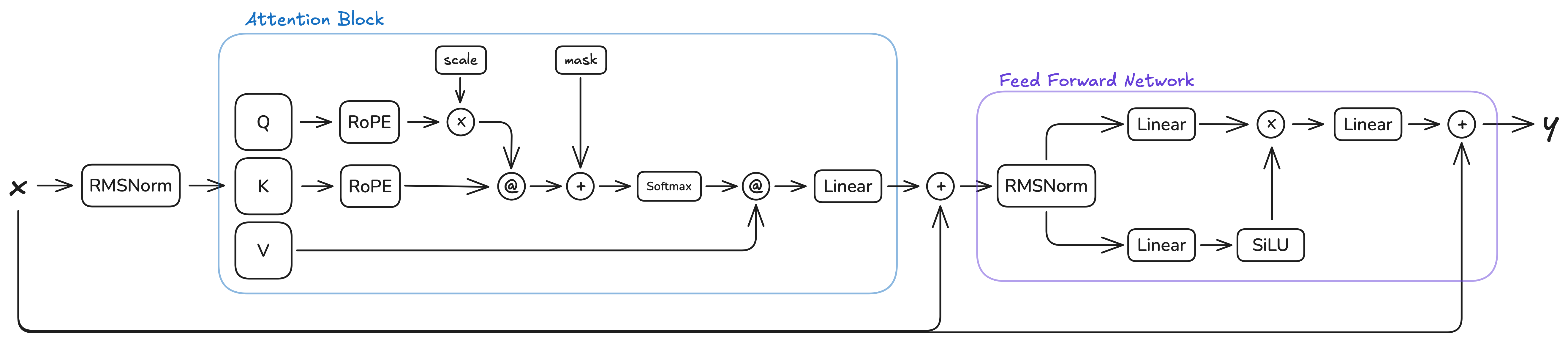

Next, let’s look at the current architecture of the transformer block and see how we can apply tensor parallelism:

This architecture has two natural places where tensor parallelism can be applied: the attention block and the FFN block. Both follow the same pattern: multiple parallel linear layers operating on the same input, followed by a single output linear layer. In the attention block, the Q, K, and V projections are sharded along the output dimension (all-to-sharded), and the output projection is sharded along the input dimension (sharded-to-all). Similarly in the FFN block, the gate and up projections become all-to-sharded layers, and the down projection becomes an sharded-to-all layer.

The intermediate operations between the linear layers (RoPE, softmax, scaled dot-product attention in the attention block, and element-wise multiplication in the FFN block) do not impede the use of our TP paradigm. These operations are either:

Element-wise operations (RoPE, element-wise multiplication): These operate independently on each element or position, preserving the sharding pattern without requiring cross-device communication.

Operations on non-sharded dimensions (softmax, scaled dot-product attention): These operate along dimensions that are not sharded (such as the sequence length or head dimensions), so they can be computed independently on each device. The attention computation

Q @ K^Tandscores @ Vwork correctly with sharded Q, K, V tensors because the matrix multiplications are performed along the sharded feature dimension, and the results remain properly sharded for the subsequent sharded-to-all layer.

To implement sharding in our Llama inference, we use shard_linear to get sharded linear layers with

distributed communication. This is easier than using shard_inplace and implementing the steps manually

in the __call__ function.

The following code shows how to shard the Attention block. The Q, K, and V projection layers are converted to all-to-sharded layers, while the output projection is converted to a sharded-to-all layer. The number of heads are also adjusted to account for the sharding:

# ... in Attention class

def shard(self, group: mx.distributed.Group):

self.n_heads = self.n_heads // group.size()

self.n_kv_heads = self.n_kv_heads // group.size()

self.wq = nn.layers.distributed.shard_linear(self.wq, "all-to-sharded", group=group)

self.wk = nn.layers.distributed.shard_linear(self.wk, "all-to-sharded", group=group)

self.wv = nn.layers.distributed.shard_linear(self.wv, "all-to-sharded", group=group)

self.wo = nn.layers.distributed.shard_linear(self.wo, "sharded-to-all", group=group)

Similarly, the FeedForward block is sharded by converting the gate (w1) and up (w3) projections to all-to-sharded layers, and the down projection (w2) to a sharded-to-all layer:

# ... in FeedForward class

def shard(self, group: mx.distributed.Group):

self.w1 = nn.layers.distributed.shard_linear(self.w1, "all-to-sharded", group=group)

self.w2 = nn.layers.distributed.shard_linear(self.w2, "sharded-to-all", group=group)

self.w3 = nn.layers.distributed.shard_linear(self.w3, "all-to-sharded", group=group)

Finally, in our load_model function, we need to apply our sharding

functions to all transformer layers when using multiple devices:

# ... in load_model function

if world.size() > 1:

# convert Linear layers in Transformer/FFN to appropriate Sharded Layers

for layer in model.layers:

layer.attention.shard(group=world)

layer.feed_forward.shard(group=world)

This allows us to use the llama inference file as normal when running

python llama.py, but now we can also run it across two (or more)

devices via mlx.launch -n 2 llama.py.